By John Puntis KONP Co-Chair, June 23rd 2020

The Westminster government has set out its plan for dealing with Covid-19. This makes plain there is no prospect of return to normality until vaccines and effective anti-viral treatments become available:

“It is clear that the only feasible long-term solution lies with a vaccine or drug-based treatment”

while at the same time acknowledging these may never materialise:

“A mass vaccine or treatment may be more than a year away. Indeed, in a worst-case scenario, we may never find a vaccine . . . . as vaccines and treatment become available, we will move to another new phase, where we will learn to live with COVID-19 for the longer term without it dominating our lives”.

The government focus is therefore only to control the epidemic and to:

“ . . . enact measures that have the largest effect on controlling the epidemic but the lowest health, economic and social cost . . rolling out effective treatments and/or a vaccine will allow us to move to a phase where the effect of the virus can be reduced to manageable levels.

begging the question – what does this look like in practice?

The answer is that we will have to live with a background level of new infections and deaths; surges in cases and reintroduction of lockdowns; public transport, schools, pubs and restaurants all operating at limited capacity; a huge rise in unemployment; considerable disruption to all areas of life.

Rather than seeing mass testing and contact tracing together with current non-pharmacological interventions as a potential Public Health solution to our problems, it is presented as something that offers only a limited prospect of success, such that it:

“may allow us to relax some social restrictions faster by targeting more precisely the suppression of transmission”

Illustrating how seriously government take the issue of ‘Test & Trace’, Johnson used the colourful analogy of the arcade game ‘Whac-A-Mole’, where plastic moles pop up at random from each of five holes and the player forces them back down by hitting them directly on the head with a mallet. The score, however, is likely to be low, since the most recent data on ‘Test & Trace’ showed that only 25% of contacts of new cases were being reached. The official SAGE committee says that 80% of the contacts of all symptomatic cases must be found and isolated in order to stop the virus spreading further.

The government lists the following as essential to any effective infection control system:

- widespread swab testing with rapid turn-around time, digitally-enabled to order the test and securely receive the result

- local authority public health services to bring a valuable local dimension to testing, contact tracing and support to people who need to self-isolate

- automated, app-based contact-tracing through the new NHS COVID-19 app to (anonymously) alert users when they have been in close contact with someone identified as having been infected

- online and phone-based contact tracing, staffed by health professionals and call handlers

As of mid-June, none of these requirements have been fully met and some seem but distant promises. There has been a major problem with testing and retrieval of results, as well as government misinformation exaggerating the extent of testing earning a rebuke from the Royal Statistical Society. Local authority public health services have been marginalised despite their expertise in contact tracing through communicable diseases and environmental health teams. £300 million was made available to support new test and trace services locally, but this amounted to an average of only around £870k for each council. There is a financial disincentive for many contacts to self isolate, recognised as a huge barrier to the effectiveness of contact tracing even by conservative MPs.

Hancock’s Half App

Mobile phone apps are part of the modern epidemiologist’s armamentarium for fighting infectious disease. South Korea has had one of the lowest case mortality rates in the world and together with widespread testing also employed mobile phone technology to track peoples movements. Early on in lockdown, Health Secretary Matt Hancock heavily promoted a home grown mobile phone app, saying it would be crucial in getting “our liberty back” and suggesting the public had a “duty” to download once available. The app, installed on a smart phone, would be designed to automatically track when users come into contact with each other, using Bluetooth technology. If someone using the app disclosed that they had developed COVID-19 symptoms, this would trigger an anonymous alert to anyone they had recently been in contact with, providing they were also using the app. This would prompt testing and self isolation, and if enough people were to use it (>60% of the population) and follow public health advice, it was expected to bring about a reduction in infections.

The security of the app was quickly challenged, and journalists reported development was being dogged by problems including a data-hungry approach, an attempt to defy Apple and Google, intra-agency bickering and a problematic test run on the Isle of Wight. The app used a centralised model, meaning that the data was not just kept on an individual’s phone, but collected centrally by government, unlike most other European countries – such as Germany, Italy and Ireland – where a more privacy-protecting decentralised model was chosen. The UK approach was heavily criticised by Amnesty International among other organisations, and lack of trust seemed likely to reduce its appeal among the public.

The deadline for being rolled out in mid-May passed quietly, and in June, the app was downgraded to only ‘the cherry on the cake’ and no longer a key part of the contact tracing strategy. On 18th June, after millions of pounds spent on technology that experts had repeatedly warned would not work, it was made clear that the project had finally been abandoned.

Track & Trace

In May, the person appointed to be in charge of the new ‘Track & Trace ‘ system was announced as Dido Harding. A businesswoman, who in 2017 had been drafted into NHS Improvement despite having no credentials in healthcare, she was misleadingly described by the prime minister as a “senior NHS executive”. Harding was severely criticised when, as chief executive officer of mobile phone company TalkTalk, there was a major data breach involving the personal and banking details of around 4 million customers. She has been described as one of the elite club of chief executives who consistently manages to fail upwards. Her other roles include being a director of the Jockey Club which runs the Cheltenham racecourse and attracted 250,000 people to the Cheltenham Festival only days before the long overdue lockdown was imposed. Her attitude to the NHS might possibly be judged by the fact she is married to John Penrose, a Conservative MP who sits on the advisory board of the think tank “1828”. According to The Mirror newspaper, 1828 argues for the NHS to be replaced by an insurance system and for Public Health England to be scrapped.

Meanwhile, the lucrative contract for contact tracing was given to Serco, a company that had just been fined £1m for failures on another government contract. In no time at all Serco had its own data breach, inadvertently revealing the email addresses of new recruits. The junior health minister, Edward Argar, happens to be a former Serco lobbyist and the company’s chief executive is Rupert Soames, grandson of Winston Churchill. Like Marley’s ghost in ‘Christmas Carol’, Serco is forever condemned to drag around a heavy weight of previous misdemeanours, including being fined £19m in 2010 over deficiencies in electronic tagging. Even optimistic NHS officials don’t expect the scheme to be fully operational until September or October, and a leaked email from Soames revealed that among other concerns, he hoped the contract would cement the position of the private sector in the NHS supply chain.

Early data on Serco’s record with ‘Test & Trace’ indicated that only a woefully inadequate 25% of contacts were identified compared with the 80% that is needed. A poll also showed that involvement of the private sector in contact tracing undermined public confidence, with 40% of those surveyed saying this made them less likely to hand over private data. An additional problem is how undocumented migrants can be brought into the system when they are worried about bills they cannot afford to pay and falling foul of the Home Office. Looking at both the disastrous app saga and the knee jerk outsourcing of contact tracing to Serco, it is difficult not to ask whether systems have in fact been designed to fail and ‘herd immunity’ somehow remains at the heart of government thinking.

An alternative view: Independent SAGE

In contrast to the Westminster government, the Independent SAGE group sees an effective COVID‐19 ‘Test & Trace’ programme as absolutely essential to the struggle to contain coronavirus infections. For good reasons, it prefers to talk of ‘Find, Test, Trace, Isolate and Support’ (FTTIS), since this encompasses all the essential features of the system. FTTIS is seen as indispensible for economic recovery, protecting livelihoods and securing longer‐term wellbeing and health provision. The key recommendations from its report are summarised below:

- LOCAL: To be effective FTTIS must be led locally, coordinated by Directors of Public Health, using both the Local Authority and NHS including health commissioners, primary care, local hospital laboratories, school nurses and environmental health officers.

- TRUST: The success of a FTTIS system is based on trust, requiring accountability mechanisms and effective community engagement.

- DATA: FTTIS findings must be embedded within existing NHS, local authority and Public Health England data structures, with rapid access to enable local response. It is important to ensure governance and safeguards for privacy and data misuse, and any supporting apps must be implemented within such a framework.

- ISOLATE and SUPPORT: This is critical if reduction in infection spread is to be realised. There must be facilities available for such isolation, material support including food and finance, and appropriate guarantees from employers, to ensure that those in isolation are not disadvantaged.

- KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS (KPI): A set of key performance indicators should be reported weekly, including data that are timely, relevant, and useful to support local decision‐making.

Details of how all this might be achieved are covered in the report, which also argues that if current restrictions are to be relaxed:

“ . . we must try to find every new case, test them, trace their contacts, and then ask the new case and their contacts to isolate for 2 weeks to prevent further spread, with the support they need to continue with their lives in these new circumstances. We must go beyond a narrow response of simply testing people suspected of being infected and tracing their contacts, which is implied by the Westminster government’s use of the term “test and trace”.

“If COVID-19 is to be eliminated, as New Zealand has shown is possible, then at least 80% of all close contacts of someone with COVID-19 infection must remain isolated for 14 days so that they are unable to pass on infection to others . . . . We argue that the current government approach to what is called Test and Trace is severely constrained by lack of coordination, lack of trust, lack of evidence of utility, and centralisation, such that achieving the goal of isolating 80% of close contacts is impossible.”

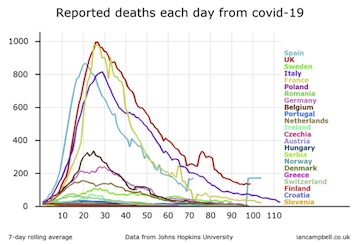

Learning from other countries

In Ireland, a group of over 1,000 scientists have launched a campaign to eradicate new cases of coronavirus, called “crush the curve”. This has drawn inspiration from countries such as South Korea, Iceland, Australia, Austria, New Zealand, Greece and China, and calls for a new strategy in Ireland aimed at complete suppression of the virus. It is argued that this is a realistic objective and can be achieved by continuing public health measures, including the use of masks, active fast contact tracing and testing, and sensible restrictions on travel. All of these must be enhanced and coordinated.

The goal would be to suppress the number of new cases to zero as soon as possible, and to keep them there. With political leadership, an agreed and scientifically sound strategy, and cooperation from the public they argue that this is potentially achievable. When this goal is reached, new infections have to be closely monitored for the foreseeable future through a robust, rapid, and vigilant FTTIS infrastructure. South Korea has managed to achieve this feat with a population similar to that of England. There are already some parts of the UK where good contact tracing has meant that infection has almost disappeared such as Ceredigion, Guernsey and the Isle of Man.

Conclusion

The Westminster government needs to set its sights higher than it currently does with ‘Track & Trace’, replacing it with a ‘Find, Test, Trace, Isolate and Support’ system that aims not just to make life manageable until an effective vaccine or anti-viral drug materialises, but to eradicate new cases of COVID-19 altogether. The Independent SAGE group points the way, and many scientists in Ireland are ready to grasp the nettle. This is why one of our key demands must be ‘bring back public health into public hands’.

AND:

Listen to Independent Sage Science Briefing (first of weekly briefings) June 26th 2020.

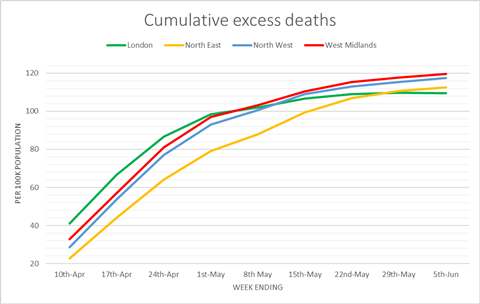

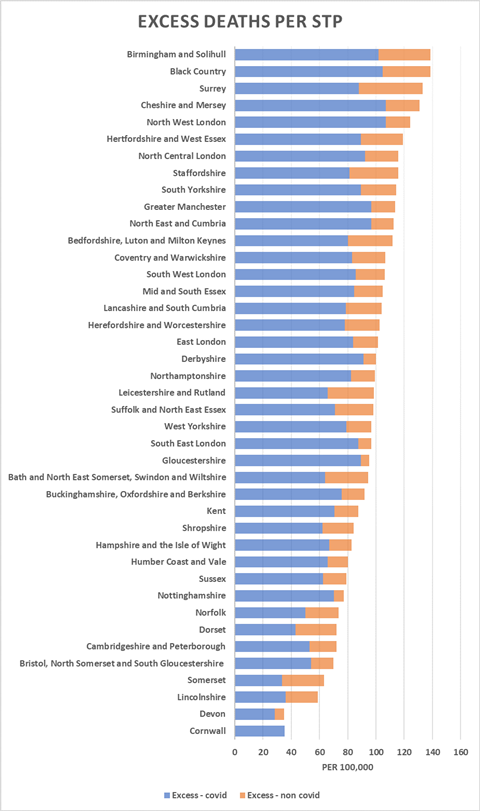

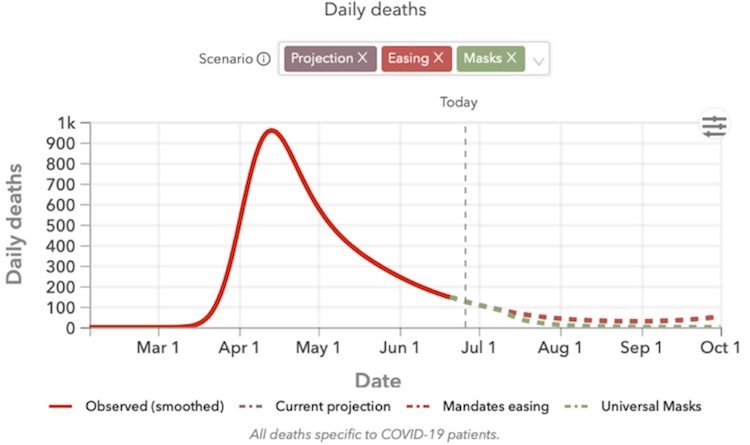

First 10 minutes statistics (with useful graphics) (Professor Christina Pagel):

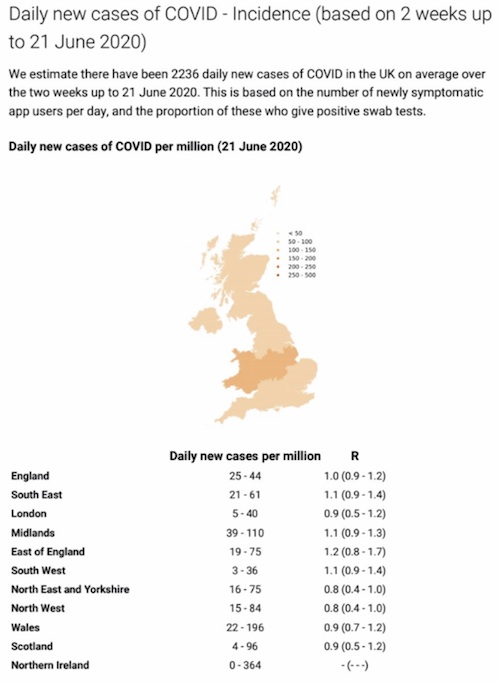

Official lab confirmed testing statistics show around 1,000 news cases per day. See the government daily statistics. But putting together estimates of newly infected cases by the Office of National Statistics surveys, University of Cambridge and King’s College London, figures are much higher: 16,500 – 30,000 new cases per week, 2,300 – 4,300 per day.

Looking at government centralised contact tracing:

a) Based on the combined estimates (ONS and others) there were about 75,000 newly infected people (yellow bar in graphic) for the 3 weeks in the period considered for the success rate of the centralised contact tracing (25 May – 17th June).

b) Of these about 40% developed symptoms , i.e 30,000 (orange bars).

c) Only just over 20,000 of these reached the contact tracing centre after a positive test. So a third of symptomatic cases had already been lost.

d) Of the 20,000 who reach the contact tracing centre, only about 72% were reached by contact tracers, i.e. about 15,000. So the contact tracers were only reaching half of the 30,000 symptomatic people in the three week period being considered.

e) Of these 15,000 people only 66% provided at least one contact, i.e about 10,000 people. So only a third of symptomatic Covid cases provided at least one contact. There is no information on how many of these contacts are then isolating, or go on to develop symptoms, or whether they are being tested or how they are doing and what kind of support they need.

Graphic from Independent-Sage presentation by Professor Christina Pagel.

This is clearly a very low success rate for 25,000 call handlers over a 3 week period.

At 56.06 minutes in, Professor Costello endorses the fundamental imperative of local test trace and track/support and importance of GPs in diagnosis etc. Following this at 58. 06, Prof Reicher stresses importance of support for people isolating. Christina Pagel underlines the need to check up on people in isolation as this is not happening at all.

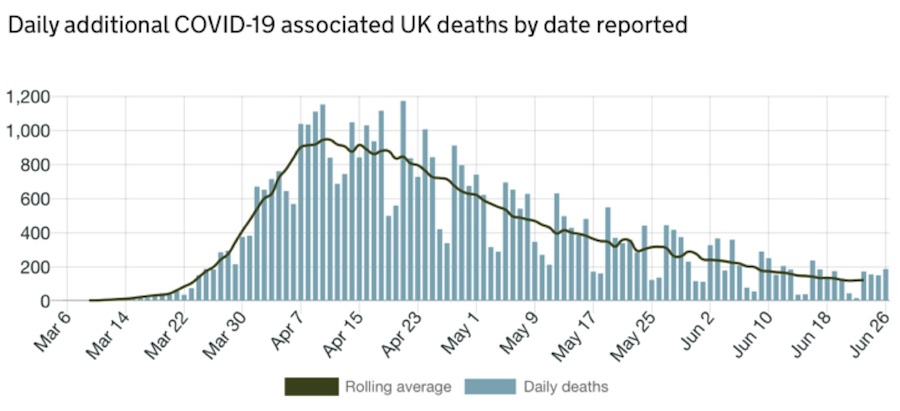

As things go from bad to worse, our prime-minister has announced almost the complete abandonment of lockdown measures – asserting that there is ‘no risk of a second wave overwhelming our NHS’. This at a time when most sources of scientific opinion are saying plan for a second wave, plan for the worst and only hope for the best. The prime-minister made this announcement on a day when 171 deaths were recorded in the UK…

As things go from bad to worse, our prime-minister has announced almost the complete abandonment of lockdown measures – asserting that there is ‘no risk of a second wave overwhelming our NHS’. This at a time when most sources of scientific opinion are saying plan for a second wave, plan for the worst and only hope for the best. The prime-minister made this announcement on a day when 171 deaths were recorded in the UK…

THE government isn’t alone in making serious errors in the pandemic. Many thousands of people might still be alive today if the scientific advice determining the timing of the lockdown had been more accurate, based on data that was available at that time, writes Private Eye’s medical correspendent MD.

THE government isn’t alone in making serious errors in the pandemic. Many thousands of people might still be alive today if the scientific advice determining the timing of the lockdown had been more accurate, based on data that was available at that time, writes Private Eye’s medical correspendent MD.