Sunday Times October 25th 2020

INSIGHT INVESTIGATION

Insight | George Arbuthnott, Jonathan Calvert, Shanti Das, Andrew Gregory and George Greenwood Sunday October 25 2020, 12.01am, The Sunday Times

Revealed: how elderly paid price of protecting NHS from Covid-19

While ministers delayed lockdown, soaring cases were putting immense pressure on hospitals. Our investigation shows officials devised a brutal ‘triage tool’ to keep the elderly and frail away.

On the day Boris Johnson was admitted to hospital with Covid-19, Vivien Morrison received a phone call from a doctor at East Surrey Hospital in Redhill. Stricken by the virus, her father, Raymond Austin, had taken a decisive turn for the worse. The spritely grandfather, who still worked as a computer analyst at the age of 82, was not expected to survive the day. His oxygen levels had fallen to 70% rather than the normally healthy levels of at least 94%. Vivien says she was told by the doctor that her father would not be given intensive care treatment or mechanical ventilation because he “ticked too many boxes” under the guidelines the hospital was using. His age, sex, high blood pressure and diabetes would all have counted against him under the advice circulating at the time. His family fear the hospital was in effect rationing healthcare while infection levels approached a peak. “He was written off,” she said.

Unusually, Vivien and her sister were allowed to visit their father one last time, provided they did so at their own risk, wore personal protective equipment (PPE) and scrubbed down afterwards.

What they saw horrified them. Vivien described it as a “death ward” for the elderly in a complaint she later made to the hospital. Inside, were eight elderly men infected with the virus who she describes as “the living dead”. As they lay “half-naked in nappies” in stifling heat, it was like a “war scene”.

While the sisters sat by their father, the man in the next bed died alone. They found an auxiliary nurse in tears outside the ward. “We said, ‘Are you all right? What’s the matter?’ And she just said: ‘They’re all going to die and no one is doing anything about it.’”

Their father died later that day without being given the option of intensive care, which the family believes might have saved him. They fear he was a victim of triaging guidelines that prevented many elderly patients from being given the care they would have received before the pandemic’s peak.

An Insight investigation can today reveal that thousands more elderly people like Raymond were denied potentially life-saving treatment to stop the health service being overrun — contrary to the claims of ministers and NHS executives.

The distressing and largely untold story of the lockdown weeks is how the NHS was placed in the impossible position of having to cope with an unmanageable deluge of patients. Despite warnings the prime minister had procrastinated for nine days before bringing in the lockdown and during this time the number of infections had rocketed from an estimated 200,000 to 1.5 million.

It meant Britain had more infections than any other European country when they took the same drastic decision, as well as fewer intensive care beds than many. Before the pandemic hit, the UK had just 6.6 intensive care beds per 100,000 people, fewer than Cyprus and Latvia, half the number in Italy and about a fifth of that in Germany, which had 29.2.

As a result, the government, the NHS and many doctors were forced into taking controversial decisions — choosing which lives to save, which patients to treat and who to prioritise — in order to protect hospitals. In particular, they took unprecedented steps to keep large numbers of elderly and frail patients out of hospital and the intensive care wards so as to avoid being overwhelmed.

In effect, they pushed the problem into the community and care homes, where the scale of the resulting national disaster was less noticeable. Downing Street was anxious that British hospitals should not be visibly overrun as they had been in Italy, Spain and China, where patients in the city of Wuhan were photographed dying in corridors.

During this time, a veil of secrecy was placed over the hospitals, and the government would emerge from the crisis of those early spring months to claim complete success in achieving its objective. “Throughout this crisis, we have protected our NHS, ensuring that everybody who needed care was able to get that care,” the health secretary, Matt Hancock, proudly declared in an email to Conservative supporters in July. “At no point was the NHS overwhelmed, and everyone who needed care had access to that care.”

But could this claim be true?

They ran out of body bags

As part of a three-month investigation into the government’s handling of the crisis during the lockdown weeks, we have spoken to more than 50 witnesses, including doctors, paramedics, bereaved families, charities, care home workers, politicians and advisers to the government. Our inquiries have unearth ed new documents and previously unpublished hospital data. Together, they show what happened while most of the country stayed at home.

There were 59,000 extra deaths in England and Wales compared with previous years during the first six months of the pandemic. This consisted of 26,000 excess fatalities in care homes and another 25,000 in people’s own homes.

Surprisingly, only 8,000 of those excess deaths were in hospital, even though 30,000 people died from the virus on the wards. This shows that many deaths that would normally have taken place in hospital had been displaced to people’s homes and the care homes.

This huge increase of deaths outside hospitals was a mixture of coronavirus cases — many of whom were never tested — and people who were not given treatment for other conditions that they would have had access to in normal times. Ambulance and admission teams were told to be more selective about who should be taken into hospital, with specific instructions to exclude many elderly people. GPs were asked to identify frail patients who were to be left at home even if they were seriously ill with the virus.

In some regions, care home residents dying of Covid-19 were denied access to hospitals even though their families believed their lives could have been saved.

The sheer scale of the resulting body count that piled up in the nation’s homes meant special body retrieval teams had to be formed by police and fire brigade to transfer corpses from houses to mortuaries. Some are said to have run out of body bags.

NHS data obtained by Insight shows that access to potentially life-saving intensive care was not made available to the vast majority of people who died with the virus. Only one in six Covid-19 patients who lost their lives in hospital during the first wave had been given intensive care. This suggests that of the 47,000 people who died of the virus inside and outside hospitals, just an estimated 5,000 — one in nine — received the highest critical care, despite the government claiming that intensive care capacity was never breached.

The young were favoured over the old, who made up the vast majority of the deaths. The chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, commissioned an age-based frailty score system that was circulated for consultation in the health service as a potential “triage tool” at the beginning of the crisis. It was never formally published.

It gave instructions that in the event of the NHS being overwhelmed, patients over the age of 80 should be denied access to intensive care and in effect excluded many people over the age of 60 from life-saving treatment. Testimony by doctors has confirmed that the tool was used by medics to prevent elderly patients blocking up intensive care beds.

Indeed, new data from the NHS shows that the proportion of over-60s with the coronavirus who received intensive care halved between the middle of March and the end of April as the pressure weighed heavily on hospitals during the height of the pandemic. The proportion of the elderly being admitted then increased again when the pressure was lifted off the NHS as Covid-19 cases fell in the summer months.

The government’s failure to properly equip the NHS with adequate PPE or testing equipment made an impossible job even harder. Not only were doctors and nurses overrun with patients, but they themselves were exposed to the virus, and the lack of testing meant that thousands had to spend time isolating at home, as they did not know if they were infected. It left hospitals dangerously understaffed.

All the while, seven Nightingale hospitals — in London, Manchester, Harrogate, Bristol, Birmingham, Exeter and Sunderland — stood mostly empty, suffering from the same shortage of intensive care staff. Those vacant beds would be used by the government to make the claim that the NHS was never overwhelmed.

Dr Rinesh Parmar, chairman of the Doctors’ Association UK, which represents frontline NHS medics, said his members had reported that many dying patients had been deprived of access to care they would have normally received at the beginning of the pandemic.

“In reality, the late lockdown allowed far more infections to spread across the country than the NHS had the capacity to cope with,” he said. “It left dedicated NHS staff in the invidious position of having to tell many critically unwell patients who needed life-saving treatment that they would not receive that treatment. Those staff will be mentally scarred for a long time as a result. They dedicate their lives to caring for people and never expected to be left in such a situation.”

Dr Chaand Nagpaul, chairman of the British Medical Association (BMA), said: “It is manifestly the case that large numbers of patients did not receive the care that they needed, and that’s because the health service didn’t have the resources. It didn’t have the infrastructure to cope during the first peak.”

The Doctors’ Association and the BMA believe there should have been an independent inquiry into the handling of the pandemic by the government so that its lessons could be applied to the second spike, which is rising fast.

Parmar added: “Without learning from this, the government appears to be repeating the same mistakes by overruling its own scientific and medical advisers, failing to take action and knowingly walking into another disaster in this second wave of the pandemic with its eyes wide open.”

‘Critical incident’ declared

In the week before the lockdown, the pandemic had hit the NHS in London — the first hotspot for the virus — like a hurricane. Despite the warnings about the threat, the government had not provided hospitals with sufficient PPE and its decision to stop contact tracing blindsided the NHS as to where and when the first wave would crash down.

The answer came on Thursday, March 19, when Northwick Park Hospital in Harrow, northwest London, declared a “critical incident”. Cases had been building at the hospital since it had been designated as the screening centre for people with Covid symptoms arriving at Heathrow.

But the population in the surrounding boroughs served by the hospital was already badly affected by the contagion. Hundreds came to the hospital seeking treatment for the virus in a fortnight and more than 30 people died in the area from infections that week alone. It meant Northwick Park had more patients than it could cope with and it began shipping them out to the surrounding hospitals.

The incident was a demonstration of how harrowing and time-consuming it would be for NHS staff to treat large numbers of patients. Nursing staff would have to sit holding the hands of dying patients in plastic gloves because their relatives were not allowed onto the wards.

Drastic measures were needed to keep the numbers down in hospitals so that clinicians could deal with the first wave of cases, which had come significantly earlier than the government had anticipated. In the last week of March, the numbers of daily deaths from Covid-19 in the capital hit triple figures and would surge even higher.

The London Ambulance Service had prepared by increasing the threshold for the severity of symptoms that a coronavirus patient would have to typically exhibit before they would be taken to hospital. The service uses a simple chart called News2, which scores each of a patient’s vital signs and gives marks on breathing rate, oxygen saturation, temperature, blood pressure, pulse rate and level of consciousness. Abnormal indications are given a higher mark. A score of five is usually sufficient for a patient to be taken to hospital.

However, on March 12 that threshold score was increased to six. “I believe it was changed because of the volume of calls and the capacity issues,” one London ambulance paramedic explained. “There were so many people to go to. There was just a period before the lockdown where no one really knew how to deal with it.” As a result, many seriously ill people were left in their homes — a policy that was dangerously selective, according to medics.

Dr Jon Cardy, a former clinical director of accident and emergency at West Suffolk Hospital, said that in normal times patients would often be referred for critical care if they scored just five on News2. “If I had a patient with an early warning score of six ,” he went on, “I’d be saying: ‘This person certainly needs hospital treatment.’ You can’t leave them at home with a cylinder of oxygen and a drip. They could easily deteriorate into multiorgan failure.”

Indeed, for many people in the initial deluge of cases, it was too late by the time their condition was deemed so serious that a paramedic team was rushed out to them. Shortness of breath was one of the key criteria for taking people to hospital, but many suffered a condition known as “happy hypoxia”. Their oxygen levels would drop dangerously without them noticing.

These people often suffered heart attacks before an ambulance could reach them — and they would not necessarily receive quick treatment because in London the average call out time for an ambulance almost trebled to more than an hour in late March.

An ambulance clinician in south London at the time said: “I saw a lot of Covid deaths in people’s homes. Too many. The critical care paramedics on call would just go from cardiac arrest to arrest to arrest. They were seeing five, six, seven of those patients a day, back to back, in their areas.”

The guidance was then changed on April 10 to advise that people scoring between three and five should be taken into hospital for assessment. The paramedic said it was changed because too many patients who needed urgent care “were just being left at home”.

Deaths from heart problems doubled compared with previous years during those early weeks of lockdown, according to figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). An adviser to the Cabinet Office said mortuary staff were shocked by the number of bodies being delivered from homes by special recovery teams that had been set up to handle the surging body count.

“The staff were seriously questioning why so many deaths were taking place at home,” the source said. “We did not explain to the public that this was the delicate balancing act — we’ve reduced the likelihood of getting an ambulance but we’ve increased the response teams to pick up bodies in people’s homes.”

Patients cleared out

In the last weeks of March, the hospitals were in the process of clearing out patients at the government’s request in readiness for the expected big surge in infections in early April. Sir Simon Stevens, the NHS chief executive, wrote to health trust chief executives outlining plans to free up a third of the UK’s 100,000 hospital beds.

His letter said he had been advised by Whitty and the government’s scientific advisory group for emergencies (Sage) that the NHS would come under “intense pressure” at the peak of the outbreak.

He asked hospitals to assume that they would need to postpone all non-urgent operations by mid-April or earlier, which would save 15,000 beds, and ordered that 15,000 “medically fit” patients should be ejected from the beds and found places in the community.

The health secretary presented emergency legislation to parliament that week to slash “administrative requirements” to help facilitate the mass discharge.

As hospitals continued to fill, the prime minister held a brainstorming session on the phone with his director of communications, Lee Cain, and key advisers from the general election and the Vote Leave campaign to create a new slogan for its fight against the virus. They came up with the words “Stay at home, save lives”, and “protect the NHS” — a key policy from the Conservatives’ successful election campaign — was suggested.

The now familiar slogan “Stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives” was launched at a Downing Street press conference by the prime minister the following day, Friday, March 20. Later, it would be heavily criticised because it could be read as a simple instruction telling everyone to keep out of hospital to preserve the NHS.

This was, after all, a key government objective, especially when it came to intensive care beds. That day, a meeting of the government’s moral and ethical advisory group (Meag) was told that Whitty’s office had been working with a senior clinicians group to devise ways to “manage increased pressure on staff and resources” caused by Covid-19. He wanted advice on the ethics of selecting who should be given intensive care treatment — and who should not.

It was total anarchy

The evening of March 23 was an extraordinary moment in the nation’s history. The prime minister had been at his most headmasterly when he sombrely announced from his antique desk in Downing Street: “From this evening I must give the British people a very simple instruction — you must stay at home.”

Two days later, Whitty dialled into an important meeting. He had asked the members of Meag, who include academics, medics and faith leaders, to consider a controversial document that had been prepared in response to his request for ethical guidance on how to select which patients should be given intensive care in the pandemic.

The document — obtained by Insight — is highly sensitive because it recommended giving a score to patients based on age, frailty and underlying conditions, to see whether they should be selected for critical care. It was intended to be used as a triage tool by doctors, and the initial version under consideration that day effectively advised that many elderly people — who were the vast majority of patients being treated for serious infections of Covid-19 — should not be given intensive care treatment.

Since any total over eight meant a patient would be given ward-based treatment only, the over-80s were automatically excluded from critical care because they were allocated a score of nine points for their age alone. Most people over 75 would also be marked over the eight- point threshold when their age and frailty scores were added together. People from 60 upwards could also be denied critical care if they were frail and had an underlying health condition.

The document — headed “Covid-19 triage score: sum of 3 domains” — had been created the previous weekend by Mark Griffiths, a professor of critical care medicine at Imperial College London, after Whitty’s request to Meag. The professor has declined to discuss the document.

Twenty members of Meag attended the meeting, with Whitty acting as an observer. Some of those present expressed concern about the use of age as an “isolated indicator of wellbeing” and questioned whether such selection might cause distress to patients and their families. One member later expressed their outrage that the triage tool discriminated against the weak and disabled.

A second version of the document, entitled the “Covid-19 decision support tool”, was also drawn up and circulated in the days after the meeting. This raised the score for specific illnesses, but lowered the marks given for age.

It was still effectively advising that anyone over the age of 80 who was not at the peak of health and fitness should be denied access to intensive care — as would anyone over 75 years old who was coping well with an underlying illness. A source says a version of this document with the NHS logo was prepared for ministers for consideration on Saturday, March 28.

According to Professor Jonathan Montgomery, Meag’s co-chairman, the documents were not formally approved or published at the time. He said they were designed only to be used if intensive care capacity had been reached — which the NHS says never happened. But Montgomery acknowledged that they had been distributed to doctors and hospitals as part of the consultation process. “We were aware that some of them were looking at that tool and thinking about how they might use it,” he said. “Some of them were using it.”

A source involved in drawing up the triage tool from the Intensive Care Society said it was sent to “a wide population of clinicians” from different hospitals, including specialist respiratory doctors dealing with the most seriously ill Covid-19 patients.

Insight’s research suggests that two versions of the triage tool were in circulation during the height of the pandemic. In late April, the largest health region in Scotland, NHS Highland, even posted a version of the original document, which excluded 80-year-olds, on the patient information section of its website, with its logo emblazoned on it. The only significant change from the original document was that women scored one less point than men.

This was marked as the document’s fifth version, which would be reviewed again in July. NHS Highland now says the publication was “in error” and was not used, but it refuses to explain how it came to be published or which part of the government or health service had passed the document on to it.

Doctors elsewhere in the country have confirmed their hospitals did use the type of age-based system proposed by this government-commissioned triage tool to prevent intensive care beds being filled beyond capacity by the elderly. One doctor said he had been told by other medics the triage tool’s age-based criteria was applied at hospitals in Manchester, Liverpool and London at that time.

The doctor described how the tool was followed so carefully at his large Midlands hospital that dozens of intensive care beds were kept empty in readiness for younger, fitter patients. He said almost all patients in his hospital aged over 75 died in the non-critical care wards without emergency treatment during that period.

If they had been given intensive care, they might have survived. In the few cases in other hospitals where patients over 80 with the virus were given intensive care, 38% survived and were discharged alive during the first wave of the outbreak, according to figures from the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre.

April the cruellest month

The death toll from the virus was rising steeply to hundreds each day by the last weekend in March. The lockdown had been a success in its first week by swiftly cutting the rate at which the virus was reproducing, but the large numbers of people who had caught the disease before the measures were introduced meant that April would indeed be the cruellest month.

There were two key places where infections remained high. The Sage committee was seriously concerned about how hospitals were becoming breeding grounds for the virus because of the lack of PPE and insufficient testing capacity to check whether staff were infected.

Many staff were unable to work after contracting the virus and others self-isolated needlessly because they or their family had symptoms that might have been ruled out by a test. NHS staff absence rates were a record 6.2%.

The other place where Covid-19 seemed to be thriving was in the place that was supposed to be sorting out such problems: No 10. As the virus swept through the cramped Georgian building, from the prime minister down, it meant that, as April began, there was a vacuum at the top of government. There were also 13,000 people in hospital with the virus and more than 600 dying each day. It was only going to get worse.

The prime minister was isolated in his flat above No 11 Downing Street with food being left at his door but was still nominally in charge. An ashen-looking Hancock, who had also contracted Covid, returned to work on Thursday, April 2, and made the bold claim that there would be 100,000 virus tests a day by the end of the month. He acknowledged that it has been his decision to prioritise giving the tests available to patients rather than NHS staff. Despite the obvious problems caused by the lack of testing, he claimed: “Public Health England can be incredibly proud of the world beating work they have done so far on testing.”

Age discrimination

While it was always inevitable that the virus-stricken prime minister would be given an intensive care bed, others were not so fortunate. The selection of patients for intensive care was already taking place and the methods being used bore a remarkable similarity to the recommendations in the triage tool that Meag members had discussed a week earlier.

This hidden triaging approach was spotted by two of the country’s leading experts in the critical care field: Dr Claire Shovlin, a respiratory consultant at Hammersmith Hospital and professor of clinical medicine at Imperial College London, and her colleague Dr Marcela Vizcaychipi, an intensive care consultant at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital who lectures in critical care at Imperial.

They were shocked to see that in the first week of April large numbers of people were dying from Covid-19 without being given access to intensive care. They did an analysis of the national figures and set out their concerns in a letter to the Emergency Medicine Journal two weeks later.

Their study showed only a small proportion — less than 10% — of the 3,939 patients who were recorded as having died of Covid-19 by Saturday, April 4, had been given access to intensive care. This was particularly worrying, according to their study, because a separate analysis of those who had survived showed the “crucial importance” of intensive care in providing support for patients “most severely affected by Covid-19”.

When they then compared the numbers of deaths from the virus in the normal wards with the number of intensive care beds said to be available in the UK, they came to a disturbing conclusion. Hospitals not only appeared to be withholding intensive care from patients who might benefit from such treatment, but they were actually being too overzealous and doing so more than was necessary given the available capacity.

This led the two experts to question what criteria the clinicians were using to choose which patients should be denied potentially life-saving treatment. In their study they expressed particular concern about “a Covid-19 decision support tool” that had been “circulating in March”, noting that it used a number of factors that meant men, the old, the frail and those suffering from underlying illnesses were less likely to be admitted to intensive care. Their description exactly mirrors the tool commissioned by Whitty and submitted to Meag.

The medics wrote: “Implementation of such tools could prevent healthy, independent individuals from having an opportunity to benefit from AICU [adult intensive care unit] review/admission by protocolised counting of variables that do not predict whether they would personally benefit from AICU care.”

Their paper concluded: “Current triage criteria are overly restrictive and [we] suggest review. Covid-19 admissions to critical care should be guided by clinical needs regardless of age.” Their study was published on May 4, but the highly selective triaging would continue — and it was already too late for many patients.

Death ward

It was a feature of the darkest weeks of the pandemic that patients would be informed of key life-and-death decisions without their families present, as the wards would be mostly off-limits to visitors because of the risk of infection.

The NHS withdrew into itself as the waves of cases hit the hospitals. It suspended the publication of critical care capacity figures, which meant nobody outside the corridors of power would be able to tell whether hospitals were being overrun, and issued a general ban on information to the media without sign off from central command.

Pressure was also exerted on NHS staff to prevent public disclosure of problems on the wards. Some trusts were alleged to have trawled staff social media accounts and given dressings-down to medics who mentioned PPE shortages or staff deaths. One surgeon working at a hospital in west London said: “There was an active drive by certain trusts to tell doctors to shut up about it because they didn’t want the bad publicity.”

So while most of the UK were hunkered down in their homes, few knew what was actually going on inside the hospitals.

When Vivien and her sister were allowed in to see their father Raymond in East Surrey Hospital they found a red “do not enter” sign emblazoned on the door to his ward and a porter guarding the entrance.

Vivien, a 54-year-old charity volunteer, says the scene was heartbreaking: “To see people just dying, all around you … It was like something out of a Victorian war scene. With nobody doing anything to help them.” Vivien’s sister was furious: “My sister said to one of the nurses, ‘Why are you allowing them to suffer? You wouldn’t treat a dog like this.’”

Their father passed away that day without being taken into intensive care. The family complained to the hospital and received a profusely apologetic letter back written by the health trust’s chief nurse, Jane Dickson, on behalf of the chief executive.

“I want you to know how sorry I am that we let your father down,” she wrote. “We have been reflecting on our initial response to the Covid-19 pandemic and I regret to say there are aspects of our care that we got wrong.” Dickson conceded that “routine tasks of supporting our patients to eat and drink suffered” because staff were “overwhelmed” and there was a shortage of staff with the necessary skills.

The letter stated the clinical team did not think “a more intensive level of care was appropriate given [Raymond’s] level of frailty”. The hospital said later in a statement that he had not been “denied the care he needed”. It added there was sufficient capacity to treat him in intensive care if this had been appropriate.

Raymond’s family find it mystifying that more was not done to get oxygen into his body. “There were other options they could have tried that may or may not have worked,” said Vivien. “But there was not that option. It was just that he wasn’t on the list.”

The family also queried why Raymond or the other patients in his ward were not taken to the Nightingale Hospital in London, which was fully equipped with oxygen and ventilators and was supposed to have a capacity of 4,000 beds — but only ever treated 54 people. “To me [the Nightingale] was like a bit of a smokescreen, a facade, because I don’t understand why they didn’t use it,” said Vivien.

The doctors on the ground say the Nightingale was beset by problems from the start. There was a struggle to recruit adequately trained staff from other hospitals that were already overstretched and medics were reluctant to refer patients because of concerns over the unknown standard of care.

One ambulance clinician who was drafted to work at the Nightingale explained that it was mainly set up to treat “younger patients who were on less respiratory support” and fewer underlying illnesses.

“But, actually, those patients were few and far between and they got prioritised on hospital intensive care units anyway because they were more likely to have a good outcome,” the clinician said. “And actually people who are a bit older or had more comorbidities were the ones we were having those more realistic discussions with.”

The NHS said it had never been the case that Nightingale hospitals were “mainly equipped” for young patients.

A stark contrast

Data obtained by Insight show that many other patients of Raymond’s age were denied access to intensive care at the height of the pandemic. The figures highlight a stark contrast that more than half of those who died of the virus in hospital during the first wave were aged over 80 and yet only 2.5% of patients of this age group were admitted to intensive care.

The data comes from the government’s best monitor of what happened in hospitals during the outbreak. It was collected from 65,000 people who were admitted to hospital with the virus up to the end of May and were analysed by the Covid-19 Clinical Information Network (Co-Cin), which reports to the Sage advisory committee.

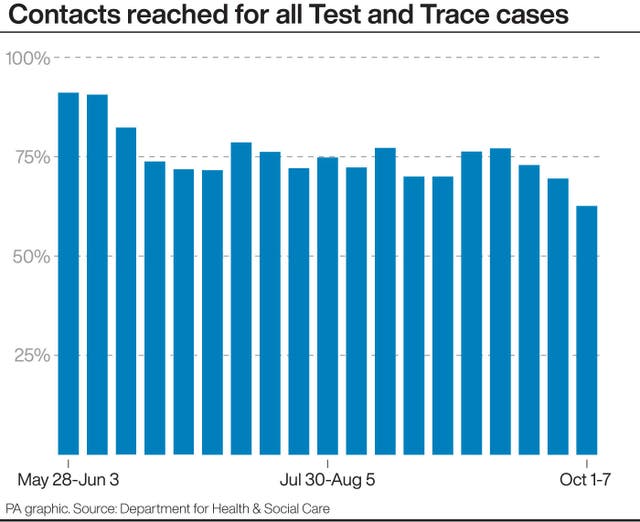

The figures show that there was a significant decrease in the proportion of people in England and Wales who had received intensive care before they died as the outbreak progressed. In the two middle weeks of March, 21% of those who died of the virus in hospital had been given intensive care treatment.

Yet as the pressure on the NHS increased through April, the proportion of critically ill patients who received intensive care before they died dropped to just 10% by the beginning of May. However, when the hospitals began dealing with far fewer patients in July, the numbers dramatically increased to 29%.

The main reason for this appears to have been that some hospitals were rationing the numbers of patients over the age of 60 who were given access to intensive care. In the middle weeks of March, 13% of that age group admitted to hospital with the virus were given an intensive care bed. By the start of May, that figure had more than halved and was down at 6%. Once again, as the pressure eased on hospitals in July, this increased back to 11%.

The official version given by ministers and the NHS was that critical care beds were still available throughout the height of the outbreak, which was certainly true for some hospitals in areas less badly hit by the virus.

But we have spoken to a number of doctors who paint a harrowing picture of the extreme choices that were being taken on the wards in virus hotspots in central and southeast England that were overrun with patients needing intensive care. At their request, we have protected their identity because they are afraid their NHS management teams could take disciplinary action against them for speaking out.

A senior intensive care doctor who was working in the same southeast region as the East Surrey Hospital where Austin died confirmed that medics were forced to choose between patients who needed intensive care beds contrary to claims that everyone received the care they required. “I don’t think the public have ever been aware of just how bad things were and indeed how bad things could get again,” she said. “Hospitals had to ration intensive care admittance. I hate to use the word ration, but it’s what was happening.”

She described how by early April her bosses realised that her hospital’s intensive care capacity would quickly be breached if they admitted all the Covid patients who would normally receive that level of care. So they began using the parameters of age, clinical frailty score and co-morbidities to help choose between patients – the same variables recommended by the government-commissioned Covid-19 triage tool.

She said that in normal times those who were very frail would sometimes not be offered invasive ventilation because of their low survival chances and the health complications the procedure can cause. But, she added, what was happening on the Covid wards was very different to that.

“The respiratory physicians and the ward medics were finding this incredibly, incredibly difficult,” she said. “They were having to turn people down for critical care and the respiratory physicians were getting upset, because usually we would give those people a shot.”

The rationing of intensive care to elderly people who would have been given such treatment if there was more capacity was “widespread” within hospitals at the time, she says. “Colleagues in intensive care reached out to me from across the country for support. They were saying, ‘This is going on at my hospital, this is feeling really bad.’”

She and fellow doctors were angered by the government’s positive messages about how the NHS was coping. “Every evening at the [televised media] briefing you just couldn’t recognise anything that they were saying. It was so discordant with what we were seeing. They’d made it all up. It was completely bizarre – picking certain statistics to highlight how well they were doing versus other countries when actually, particularly in London, it was an absolute car crash.”

London bore the initial brunt of the first wave with the highest number of intensive care admissions and the doctors found the extent of the triaging they were forced to do particularly tough. A surgeon working at a hospital in the west of the city said: “A lot of patients who we will in normal times say, ‘Okay, we’ll admit them to intensive care to give them a chance in the knowledge that they might well not make it’ … for those patients that chance was not given.”

This is confirmed by Professor Christina Pagel, director of University College London’s Clinical Operational Research Unit. “There is no doubt that there are people that would have got intensive care at the beginning of March or in June that didn’t get it in April because of capacity,” she said.

By Wednesday April 8, the numbers of people dying of the coronavirus each day exceeded a thousand and hospitals in other areas were beginning to take drastic measures. A senior doctor working in the intensive care wards of one of the major hospitals in the Midlands has described the difficult decisions that were taken.

“We were limited by the capacity, the number of beds we had and the worry that if we filled our intensive care units up with frail, older patients we’d be unable to take the younger patients,” he recalled. “As we got busier, our admission criteria and the people that were being admitted significantly changed to not admitting those that were elderly.”

He said his hospital’s admission criteria was based on a version of the ‘Covid-19 Decision Support Tool’ which had been prepared for ministers on March 28. The management of his NHS trust had sent the tool to medics saying “it had been produced to help guide decision-making regarding admissions to critical care,” he said.

As a result of applying the scores in the tool, he says, “we got to the point where we almost didn’t have anyone in critical care who was over 75. Whereas we had been admitting that age group at the beginning.” But the tool was applied so rigorously that the hospital kept dozens of intensive care beds free that were not used for the over-75s.

The elderly, he says, were not even offered non-invasive ventilation as they were left to die in the non-intensive care wards. As a result, 90% of the hospital’s deaths from the virus happened on the wards and just 10% received intensive care during the height of the pandemic in April.

He admits that his colleagues would often have to tell a “white lie” to patients suggesting it was in their best interests to be cared for on the wards. “But the reality of the situation was actually it was because we were facing multiple admissions of younger, fitter patients at that point, and we just couldn’t accommodate the elderly at the rate that they were coming in.”

But he says it was easier to exclude the elderly from intensive care because the fear of infection meant there were no families visiting who might challenge the decision. “Certainly for some of the fitter 75 year olds we could have taken, we should have taken [into intensive care] and we probably would have done as a result of pressure from families,” he said.

This selective approach continued into May and the elderly were only admitted to intensive care again when patient numbers began to drop in the summer.

The clinician blames the prime minister’s late lockdown for placing doctors in such an invidious position during those months. “We would have had fewer patients admitted in that short period of time so we would have been able to offer the best in terms of intensive care capacity for each and every single one of them.”

Identify the frail

The prime minister was touch and go for a while but was able to return to the ward from intensive care on Thursday April 9. On that day an extraordinary document was distributed by the Buckinghamshire NHS Trust asking clinicians and GPs to urgently “identify all patients who are frail or in the latter stages of life and score them based on their level of frailty”. The purpose was to draw up a list of those who might stay at home when they became seriously ill rather than be taken to hospital.

The document made clear that the move was necessary because intensive care was “expected to far outweigh capacity by several thousand beds over the next few weeks in the southeast region due to Covid-19” and that there was “a limited staff base to look after sick patients in our hospitals.” It said the approach it was setting out was being adopted by clinical commissioning groups across England.

The trust was asking doctors to scour the lists it was providing from registers of care home, palliative, frail and over 80-year-old patients and give them a score. If the patients scored seven on the frailty scale – which was anyone dependent on a carer but “not at risk of dying” – the trust recommended that it would be better that they remained at home rather than be taken into hospital.

The document said that the decision should take into account the patient’s circumstances and family’s wishes when deciding on hospital admission but it was “ultimately a decision for the clinicians involved”. In a statement last week the Buckinghamshire trust said every patient who needed hospital treatment was admitted.

However, this type of selection made some doctors feel uneasy. One GP in Sutton, south London, described how his health authority had made “inappropriate” demands on his practice to contact elderly and frail patients to discuss their future care plans in a way that ruled them out for hospital treatment and told him “we’re going to be analysing the numbers.”

He said the authority had identified dozens of his practice’s patients who would be asked to accept ‘do not resuscitate’ orders or agree that they would forgo hospital care in the future. The health authority instructed him to talk to the patients and log their decisions on a centralised system named Coordinate My Care which ambulance staff could then access to see whether a patient had opted out of hospital care, according to its website.

The doctor said he was “told to get a certain percentage” of patients on the authority’s list “signed up”. In the end, he only contacted a handful because he felt the conversation was “damaging to patient-doctor relationships” and he says his practice was ticked off by the health authority for not fulfilling their instruction.

Similarly difficult conversations appear to have taken place across the country. The Coordinate My Care system has been in operation for ten years but there was a huge increase of 34,000 patients added to its list in the first six months of this year.

Last week, Dr Dino Pardhanani, GP lead for Sutton on behalf of NHS South West London, defended the approach. He said the discussion of future care plans with patients was “established best practice and the Covid-19 outbreak did not change that”.

As the crisis was reaching its height on April 10, Good Friday, NHS England weighed in with its own advice to health authorities setting out the groups of elderly people across the country who it said “should not ordinarily be conveyed to hospital unless authorised by a senior colleague”

The list was very broad. It included all care home residents and patients who had asked not to receive an intravenous drip or to be resuscitated. It effectively suggested that those who had accepted do not resuscitate orders might be denied general hospital care. There was also an exclusion for dementia patients with head injuries and people who had fainted and appeared to have “fully recovered” – but only if they were over the age of 70.

The advice was withdrawn in just four days after there was an angry backlash. Martin Vernon, the NHS’s former national clinical director for older people, said it had been a “flagrant breach” of equality laws. “It seemed to suggest that people in care homes and older people generally have less value, and therefore it’s quite reasonable to exclude them from the normal pathway of care,” he said.

An NHS statement said the advice had been brought in to make sure that ambulance crews consulted with senior control room colleagues about whether patients could be more safely treated outside of hospital.

But there was no doubt that the measures to protect the NHS did have a significant effect. Just 10% of the 4,000 Covid deaths registered in the last week of March and first week of April occurred outside hospitals, according to figures from the ONS. Yet in the fortnight spanning the end of April and beginning of May, some 45% of the 14,000 people who died of the virus had not been taken into hospital.

They were people like Brian Noon, a “fit and strong” 76-year-old RAF veteran, who had tested positive for the virus after attending the A&E department at the Lancaster Royal infirmary on Good Friday.

The hospital sent Noon home and arrangements were made for him to be checked twice a day by a rapid response nursing team who were already visiting to monitor his terminally ill wife, Desley, 77. On Easter Sunday, his daughter Kerry says she spoke to one of the nurses and was told she needed to talk to him about agreeing to a “do not resuscitate” order. The nurse warned, Kerry says, that an ambulance would refuse to take him to hospital if he did not have such an order in place.

The family initially decided not to discuss the issue with Noon because he had a “fear of death” and it might upset him. The next day the nurse returned to say their father would no longer be sent to hospital if his condition worsened. “It was not a discussion,” his eldest daughter Maria said. “We were told there had been a change to the plan and dad wouldn’t be going to hospital.”

They were not aware at the time just how sick their father had become. It was only weeks later that they were shown the rapid response team’s logs which recorded a plummet in his oxygen from 91% on Easter Sunday to 79% the following Tuesday.

The guidance from the British Thoracic Society is that oxygen levels below 94% are abnormal and require assessment for urgent treatment. However, his nursing team had repeatedly written “oxygen therapy not required” in his records and despite his desperate condition noted that “no further escalation [of treatment] is intended or considered appropriate”.

His oxygen levels had dropped to 44% when he died on Wednesday April 15. His family were left in the dark as to why he was not given the treatment he required. His GP told them that “vulnerability scores” were being used by the health service in the area but it is not known whether Noon was assessed in this way.

If they had applied the Covid-19 Triage Tool seen by Insight, Noon would have been excluded from intensive care because of his age, frailty and diabetes. The family now wants a full explanation.

“Dad did not receive timely and crucial medical care and as a direct result, he died a horrific and excruciatingly painful death,” said Maria. “We feel like Dad’s been murdered. They were killing off the elderly and the vulnerable. If you’re elderly, don’t you need more care, don’t you need more compassion?”

Dr Shahedal Bari, medical director of University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust, which was responsible for Noon’s care, said it was “working with the family to answer all of their questions”.

Ultimately thousands of frail and elderly people across Britain died at home without hospital treatment. Caroline Abrahams, director of the charity Age UK, has accused the government of being too fearful of the “endless news coverage of people dying outside in hospital corridors or banked up in ambulances” and alleges that older people were “considered dispensable” as a result. “The lack of empathy and humanity was chilling. It was ageism laid bare and it had tragic consequences,” she said.

Carnage in care homes

The discharge of up to 25,000 hospital patients into care homes during the pandemic’s height was becoming a highly controversial move. By Friday April 17 there had been almost 10,000 excess deaths in the homes and yet the policy of allowing patients to be transferred into them without first being tested for the virus had only ceased the day before.

Indeed hundreds of patients were also being sent to homes even though they had tested positive. In response to a request from the department of health to make more beds free in hospital, councils such as Bradford instructed the care home sector to bear the responsibility for looking after hospital patients for the duration of their illness.

Such policies wreaked havoc in the homes where staff had even less protective equipment than the hospitals and would often spread the virus as they worked shifts in different premises. A third of all care homes declared a coronavirus outbreak, with more than 1,000 homes dealing with positive cases during the peak of infections in April, according to the National Audit Office. During the three months of the first wave of the pandemic, 26,500 more people died in care homes than normal.

Many of those who died were simply refused care. David Crabtree, an owner of two care homes in West Yorkshire, is angry about the way many of his residents were left to die and were denied access to hospital.

A hospital patient had been forcibly discharged back into one of his homes without a test and developed symptoms for Covid-19 at the beginning of April. As the patient’s condition deteriorated, the home called an ambulance but a clinician on the end of the phone refused to send one. “We were told there was a restriction on beds and to treat as end of life,” Crabtree said. The resident died a few days later in the second week of April.

The single infection had already spread quickly to others in the home. In the days that followed a total of seven more residents died from the virus and not one was admitted to hospital. “I couldn’t believe what we were being told,” he said, “they were denying people because of age.”

But in the middle of the month, the policy of the hospital changed and infected residents were admitted. “The peak dropped so I don’t think there was pressure on beds. After April 15 we were able to get people into hospital.” He said five infected residents from his home were admitted to hospital at the end of the month and they all survived — raising the question as to whether the other eight would have still been alive if only they had been treated.

An Amnesty International report published this month found that the numbers of care home residents admitted to hospital decreased substantially during the pandemic, with 11,800 fewer admissions during March and April in England compared to previous years.

Medics have also described how the care home sector was left to fend for itself. An intensive care doctor in the Midlands said: “I can’t remember seeing anybody from a care home who had tested positive who was brought into hospital, not a single one.”

Turned away

At Johnson’s first prime minister’s questions in the Commons on Wednesday May 6 after his return to work the previous week, he conceded that there had been a tragedy in the care homes. “There is an epidemic going on in care homes, which is something I bitterly regret,” he said.

However, there were still very sick people who were being turned away from hospitals. Betty Grove, 78-year-old grandmother from Walthamstow, northeast London fell ill at the end of April with a cough and low oxygen levels and went to Whipps Cross Hospital in east London on the advice of her GP.

The hospital found she had pneumonia and a collapsed lung and, yet, still sent her home four hours later because, according to her daughter Donna, they feared she might become infected with Covid-19. She may well have already had the virus, especially given her symptoms. But, Donna says the hospital refused to test her mother because they would have to admit her to do so. It was a Catch-22.

Over the next ten days, Betty, a retired Co-op worker of 25 years, “grew weaker” and began struggling for breath. Donna says she called her local trust’s rapid response team repeatedly — sometimes twice a day — asking for help for her mother. “I was insisting that they needed to come out and check her,” she said.

Betty died at home of pneumonia on May 15. Her family believes she would have survived if she had been admitted when she first went to hospital. Barts Health NHS Trust has since apologised to the family for Grove’s treatment and launched an internal investigation.

Donna said: “I get that they did have enough on their plate. They had Covid … but it doesn’t mean to say they can push these people aside and just let them go home to die.”

Tragic delay

The first wave’s death toll left tens of thousands of families across the country in mourning. But for many that sadness has turned to anger as they have learned more about how their loved ones died and question whether they could have been saved with better medical care.

The families who spoke to this newspaper have great sympathy with NHS staff who worked night and day risking their own lives while isolating themselves away from their own families. More than 600 health service staff have themselves died from Covid-19. A mental health crisis is now feared within the NHS because of the emotional strain of being forced into making so many harrowing life and death decisions.

Instead the focus of the relatives has fallen on the government whose late lockdown allowed so many to become infected. More than 2,000 families have formed the Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice UK group and in the summer they wrote to the prime minister and the health secretary demanding an immediate statutory inquiry into their handling of the pandemic. They asked to meet Johnson and Hancock to put their questions in person. Both requests have been refused by the government’s lawyers.

Elkan Abrahamson, the human rights lawyer representing the group, said the families are driven by a desire to prevent more unnecessary deaths during this second wave of the pandemic. But, he added, the government’s legal department had “clearly been told to ferociously fight any attempt to elicit the truth about the first wave”.

The government’s response

In response to this article, a statement for the Department of Heath said: “From the outset we have done everything possible to protect the public and save lives.

“Patients will always receive the best possible care from the NHS and the claim that intensive care beds were rationed or that patients were prevented from receiving necessary care is false. Doctors make decisions on who will benefit from care every day, as part of normal clinical decision-making. “Since the beginning of this pandemic we have prioritised testing for health and care workers and continuously supplied PPE to the frontline, delivering over 4.2 billion items to date. We have been doing everything we can to protect care home residents including regular testing and ring-fencing over £1.1billion to prevent infections within and between care settings.”

Professor Stephen Powis, NHS national medical director, also issued a statement saying that the health service “cared for more than 110,000 severely ill hospitalised Covid patients during the first wave of the pandemic” and older patients had “disproportionately received NHS care – over two thirds of our Covid inpatients were aged over 65.”

He said: “The NHS repeatedly instructed staff that no patient who could benefit from treatment should be denied it and, thanks to people following Government guidance, even at the height of the pandemic there was no shortage of ventilators and intensive care.

“We know that some patients were reluctant to seek help, which is why right from the start of the pandemic the NHS has urged anyone who is worried about their own symptoms or those of a loved one to come forward for help.”